Magnet for Artists and Expats...Inspired Sterling Dickinson

In 1937, after several months spent traveling through Mexico, Stirling Dickinson, a graduate from Princeton, got off a train in San Miguel de Allende, an arid, down-on-its-luck mountain town 170 miles northwest of Mexico City. Taken from the ramshackle train station by a horse-drawn cart, he was dropped off at the main square, El Jardín. At the eastern side of the square stood the Parroquia de San Miguel Arcángel, an outsize, pink-sandstone church with neo-Gothic spires, quite unlike Mexico's traditional domed ecclesiastical buildings. "There was just enough light for me to see the parish church sticking out of the mist," Dickinson would later recall. "I thought, My God, what a sight! What a place! I said to myself at that moment, I'm going to stay here."

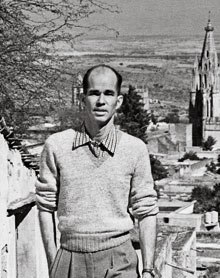

Founded in 1542, the settlement of San Miguel had grown rich from nearby silver mines during centuries of Spanish rule, then fell on hard times as the ore was depleted. By the time Dickinson got there, the War of Independence from Spain (1810-21) and the even bloodier Mexican Revolution (1910-21) had further reduced the town to 7,000 inhabitants—less than a quarter of its population in the mid-1700s. Houses languished in disrepair, with shattered tile roofs and crumbling, faded walls. Dickinson made his home in a former tannery on San Miguel's higher reaches and soon became a familiar sight, riding around town on a burro. For the next six decades, until his death in 1998, he would lead a renaissance that would transform tiny San Miguel into one of Latin America's most magnetic destinations for artists and expatriates, most of them American, looking for a new venue—or a new life.

"Stirling Dickinson is without doubt the person most responsible for San Miguel de Allende becoming an international art center," says John Virtue, author of Model American Abroad, a biography of Dickinson. Although only an amateur painter himself, Dickinson became co-founder and director of the Escuela Universitaria de Bellas Artes, an art institute that he opened in a former convent only a few months after his arrival.

During World War II, Dickinson served with U.S. Naval Intelligence in Washington and the Office of Strategic Services (forerunner of the CIA) in Italy. Returning to San Miguel after the war, he recruited hundreds of young American veterans to study at Bellas Artes on the G.I. Bill of Rights. In the postwar years, non-artists and retirees, as well as painters and sculptors, were drawn to the city; today, one out of ten residents is an expat. Eighty percent or so are retirees; the others oversee businesses, from cafés and guesthouses to galleries and clothing stores. Most of these expats—some of whom have Mexican spouses—volunteer at more than 100 nonprofit organizations in San Miguel, including the library and health care clinics.

"This mestizaje—cultural mixing—has profoundly changed and benefited both sides. SMA owes a huge debt of gratitude to Stirling Dickinson for helping this come about and for raising San Miguel's profile in the world."

Walking the cobblestone streets flanked by stucco houses painted vivid shades of ocher, paprika and vermilion, one passes lively squares full of street musicians and vendors hawking tacos. In the distance rises the Sierra de Guanajuato. In 2008, San Miguel was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site, in large measure because of its intact 17th- and 18th-century center.

Dorothy Birk—Dotty Vidargas—was among the first of the young Americans to answer Dickinson's call, in 1947.

Vidargas grew up in Chicago, a block away from Dickinson. She says he had three passions: art, baseball and orchids. At Bellas Artes, she recalls, he formed a baseball team that won 84 games in a row and captured several regional amateur championships in the 1950s. He traveled throughout Mexico and the world to collect wild orchids, breaking three ribs in a fall during a 1960s expedition to southern Mexico's Chiapas highlands. An orchid he discovered there in 1971 was named after him—Encyclia dickinsoniana.

In 1942, in her sophomore year at Wellesley College, Vidargas left academia to enlist in the war effort, eventually serving as a Navy recruiter and, later, as an air controller for the Army Air Forces outside Detroit. After the war, she enrolled at the American Academy, an art institute in Chicago. But in 1947 she decided to spend her G.I. Bill subsidies in San Miguel. "My mother knew Stirling and figured it would be all right for me to go," she says. She was one of 55 veterans accepted at Bellas Artes that year. More than 6,000 veterans would apply to the school after the January 1948 issue of Life magazine called it a "G.I. Paradise," where "veterans go...to study art, live cheaply and have a good time."

But Vidargas' first impression was well this side of paradise. Arriving by train in the pre-dawn darkness, she checked into a hotel where electricity and running water were sporadic. Many of the surrounding buildings were near ruins. Burros outnumbered cars; the stench of manure and raw sewage was overpowering. "I was cold, miserable and ready to board the next train home," she recalls. But she soon found more comfortable student lodging and began her Bellas Artes course work. Between school terms, she traveled with fellow students and Dickinson throughout Mexico.

She even joined the local bullfighting circuit as a picador, or horseback-mounted lancer. "It was after a few drinks, on a dare," Vidargas recalls. Soon "la gringa loca" ("the crazy Yank"), as she was becoming known, was spending her weekends at dusty bullrings, where her equestrian prowess made her a minor celebrity.

Meanwhile, some members of the town's conservative upper class were outraged by the American students' carousing. The Rev. José Mercadillo, the parish priest, denounced the hiring of nude models for art classes and warned that the Americans were spreading Protestantism—even godless Communism.

In fact, in 1948, Dickinson recruited the celebrated painter David Alfaro Siqueiros, a Communist Party member, to teach at Bellas Artes. There he lashed out at his critics, far exceeded his modest art-class budget and eventually resigned. Siqueiros left behind an unfinished mural depicting the life of local independence leader Ignacio Allende, whose last name had been appended to San Miguel in 1826 to commemorate his heroism in the war. The mural still graces the premises, which today is occupied by a cultural center.

Apparently convinced that Communists had indeed infested Bellas Artes, Walter Thurston, then the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, blocked the school's efforts to gain the accreditation necessary for its students to qualify for G.I. Bill stipends. Most of the veterans returned home; some were deported. Dickinson himself was expelled from Mexico on August 12, 1950, although he was allowed back a week later. "It was the low point in relations between Americans and the locals," recalls Vidargas. "But my situation was different, because I got married."

José Vidargas, a local businessman met his future bride at a bowling alley, one of many postwar fads to invade Mexico from the United States. Some of his relatives wondered about his plans to marry a gringa. "Suddenly, I had to become a very proper Mexican wife to be accepted by the good society families," recalls Dorothy. The couple had five children in seven years, and Dorothy still found time to open the first store in San Miguel to sell pasteurized milk; the real estate agency came later. Today, three sons live in San Miguel; a daughter lives in nearby León; one child died in infancy.

By 1951, the various controversies had closed down Bellas Artes, and Dickinson became director of a new art school, the Instituto Allende, which soon became accredited and began granting Bachelor of Fine Arts degrees. Today, the nonprofit school, attended by several hundred students annually, encompasses a fine-arts degree program, a Spanish-language institute and traditional handicraft workshops.

In 1960, Jack Kerouac, the novelist who had catapulted to fame three years earlier with the publication of On the Road, went to San Miguel with pals Allen Ginsburg and Neal Cassady. Ginsburg read his poetry at the Instituto Allende, while Kerouac and Cassady spent most of their time downing tequilas at La Cucaracha, a traditional Mexican cantina that remains popular to this day. The trio remained only a few days, but in 1968, Cassady returned to San Miguel, where he died at age 41 from the effects of alcohol, drugs and exposure.

The plaintive recordings of Pedro Infante, still Mexico's most popular country singer more than a half century after his death, can be heard some mornings at San Miguel's largest traditional food market, the Mercado Ignacio Ramírez. Vendors display varieties of chile, red and green prickly pears, black and green avocados, orange and yellow melons, tropical fruits including mamey, with its pumpkin-hued flesh, and guayaba, whose texture resembles a white peach. Nopales (cactus leaves shorn of spines) are stacked alongside Mexican herbs, including epazote, used to flavor black beans, and dark red achiote seeds, an ingredient in pork and chicken marinades.

By the early 1980s, Dickinson had begun to distance himself from the growing number of Americans. "Stirling must have shuddered the day he saw the first tourist bus arrive in San Miguel and disgorge tourists wearing shorts," wrote biographer Virtue. "These were exactly the type of people he railed against in his own travels abroad." In 1983, Dickinson resigned as director of the Instituto Allende, where, during his 32-year tenure, some 40,000 students, mainly Americans, had matriculated. Increasingly involved with the Mexican community, he oversaw a rural library program that donated volumes from San Miguel residents to village schools. He also began to support financially the Patronato Pro Niños—the Pro-Children Foundation—an organization providing free medical service and shoes for impoverished rural youngsters.

On the night of October 27, 1998, the 87-year-old Dickinson was killed in a freak accident. As he prepared to drive away from a Patronato Pro Niños meeting held at a hillside house, he accidentally stepped on the gas pedal instead of the brake. His vehicle plunged down a steep embankment; Dickinson died instantly. More than 400 mourners, including foreigners and Mexicans from the countryside, attended his funeral. He was buried in the foreigners' section of Our Lady of Guadalupe Cemetery, just west of San Miguel's center. Today, a bronze bust of Dickinson stands on a street bearing his name.

Inspired J K