Mexico’s ‘Mayan Train’ Is Bound for Controversy

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s signature rail project would link cities and tourist sites in the Yucatan with rural areas and rainforests.

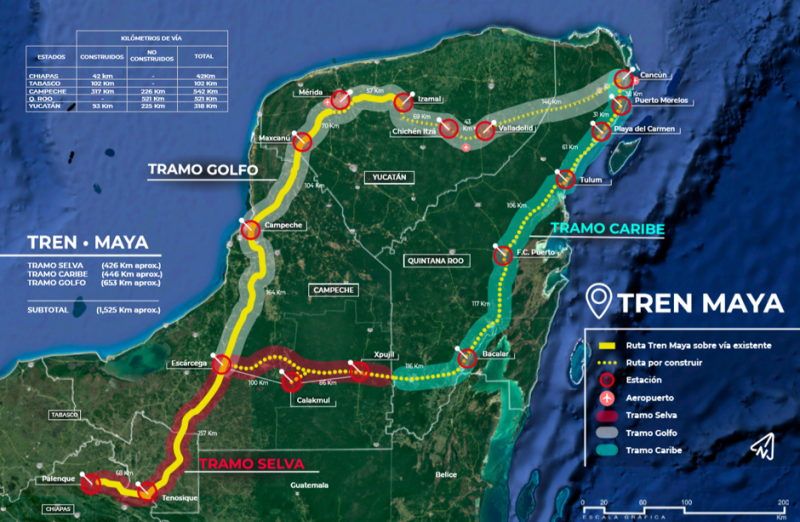

Running more than 900 miles from the beach resorts of Cancún to the Mayan archaeological site at Palenque, the $6.5 billion rail project would link towns, cities, and tourist attractions in five southern states. Planners expect a ridership of 8,000 passengers a day, evenly split between locals and tourists.

Speaking in his folksy style during the ritual, López Obrador, a former mayor of Mexico City elected in 2018 as the first left-wing president in modern Mexico, emphasized how the train would serve as a critical investment in Mexico’s economically depressed southeastern states. “This is an act of justice, because this region has been the most abandoned,” said López Obrador, who made Mexico’s stark income inequality a centerpiece of his campaign. “The moment of the southeast has arrived, and it’s just in time. That’s why [the train] is a very important public works project.”

The Mayan Train represents just one part of López Obrador’s ambitious agenda to reduce poverty and integrate the rural and indigenous populations that have been left out of development in the NAFTA era. But since its announcement in February 2018, the project has sparked fierce debate in Mexico. Some see it as a promising new tourism and economic development tool. And as the most ambitious new passenger rail line to be built in Mexico in decades, there are hopes that the Mayan Train might even usher in a new golden age of Mexican train travel. But others fear it’s destined to become another of Mexico’s notorious white elephant projects—and an ecological disaster in one of the world’s most environmentally and archaeologically sensitive places.

López Obrador is hardly the first politician to dream of connecting the Yucatan Peninsula by train. Natural gum (chicle) was the region’s principal export in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and private companies constructed their own railroads to move gum from the rainforest interior to nearby ports. In the 1920s, Amado Aguirre, governor of the newly formed federal territory Quintana Roo, wrote to the president calling for a train to be built from Quintana Roo to Yucatan. But a decade later, the first highways were built in the Peninsula; railroads lost the race.

More recently, López Obrador’s predecessor, Enrique Peña Nieto, set out to build a train from Cancún to Mérida at the start of his administration in 2012, but canceled that project amid austerity cuts in 2015. His other major rail project was a train linking Mexico City and Toluca—a span of just 35 miles. That one is still under construction, six years later; activists have protested trees being cut down for its construction and the project’s budget has ballooned by 50 percent.

Despite such previous setbacks, López Obrador has laid out an even more ambitious railroad agenda, promoting the development of Mexico’s scanty passenger rail infrastructure as a candidate and now as president. Ever since his first presidential bid in 2006, he’s promised to build high-speed train lines around the country. In 2012, he said trains would be the “motor of development” in his presidency.

That’s the thinking behind the Mayan Train scheme, which was masterminded in a bid to link the rural communities of the Yucatan and encourage tourists to explore beyond the Maya Riviera, as the string of beach destinations along the Caribbean coast is known. The project is also designed to create more regional jobs, so people no longer have to migrate from rural areas into the tourism centers to work low-wage jobs at hotels and resorts. According to the Quintana Roo Department of Labor, as many as 300 people move to the northern part of Quintana Roo every day in search of employment.

Spearheading the Mayan Train scheme is the National Fund for Tourism Development (FONATUR), a federal agency responsible for tourism infrastructure led by Rogelio Jiménez Pons. Thus far, the federal government has not carried out an exhaustive cost-benefit analysis for the train. What little the government has specified about the project relates to costs. López Obrador says that Mexico’s national tourism tax will provide $1.5 billion in initial funding and the train will be built over several stages during his six-year term. In a January interview, Jiménez Pons named Canadian company Bombardier, the China Railway Construction Corporation, and the Spanish firm Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles (CAF) as a few possible bidders on the project.

FONATUR will use both existing railroad tracks and construct new ones. Where new tracks must be built, FONATUR assures they will use land that is already federal property, either alongside highways or electrical transmission lines, to avoid deforestation and land disputes. But indirect environmental impacts are harder to control for, critics of the project have pointed out: New commercial or residential development near stations could cause deforestation and tax public services in the region.